You’ve heard of Sarah Burton and Alexander McQueen, but have you heard of Norman Hartnell? Yeah, we didn’t think so. Hartnell was once one of the most renowned fashion designers in the world, mainly because he designed two of the most famous wedding dresses of all time: the bridal dresses of Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret. Those gowns helped rocket him to international fame and drew attention to his other, excellently constructed, dresses. However, these days, his name has been largely forgotten.

While he may be known in fashion-savvy circles, otherwise, Hartnell has been reduced to a historical footnote. But thanks to The Crown, which reenacts both Queen Elizabeth and Margaret’s weddings, Hartnell’s designs are suddenly back on the radar. Here, we take a brief look back at the life and work of the British royals’ favorite designer.

Born in London in 1901, Hartnell was a visually-inclined child, who grew up to study architecture at Cambridge University before ultimately dropping out, as Daniel James Cole and Nancy Deihl’s book, The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850, explains. In the early 1920s, Hartnell established a fashion design business and created works for theater and early screen sirens

He received his first commission from the British royal family in 1935, when he was tasked with creating the wedding dress and trousseau of the future Princess Alice, wife of the Duke of Gloucester. The then-Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret, who served as bridesmaids, first wore his designs for this wedding as well. Queen Elizabeth’s mother, known later as the Queen Mother, became a fan of Hartnell’s work and frequently wore his designs during her own tenure as Queen, too. However, Hartnell was not solely focused on dressing the Windsors. During World War II, he helped participate in rationing efforts and during the first half of his career, he was covered in both in British and American Vogue.

After World War II, Hartnell’s ballgowns shone even brighter. With the introduction of Christian Dior’s A-line and fabric-emphasizing “New Look,” and the rise of the strapless dress, the fashion climate was ripe to accept Hartnell’s aesthetic. During the late 1940s, Hartnell traveled in South America, showing his designs to high-profile local clients.

But it was the work he completed upon his return that truly solidified his place in fashion history. In 1947, Hartnell designed the then-Princess Elizabeth’s wedding dress. Post-war rationing was still in place back then, and Princess Elizabeth famously had to save up coupons in order to be able to purchase it. The gown (which was recreated in the very first episode of The Crown), was seen by people all around the globe.

In 1953, Elizabeth again commissioned Hartnell, this time to make her coronation dress. It had a similar silhouette to the gown she wore for her wedding, and featured botanical embroidery that referenced plants native to different regions of the Commonwealth. But his work for the coronation wasn’t limited to the gown worn by Queen Elizabeth herself; he made gowns for other royal women in attendance, including Queen Elizabeth’s ladies-in-waiting, and her sister Princess Margaret. Aside from his work for the Queen in the 1950s, Hartnell also started including maternity designs in his collections—a rarity for the time.

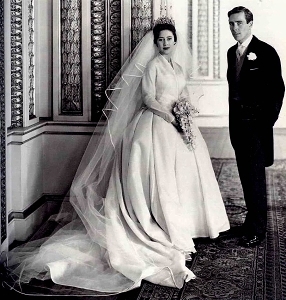

In 1960, Princess Margaret married the future Lord Snowden. (As fans of The Crown know, her engagement to the British photographer happened after she found out her former fiancé, Group Captain Townsend, was getting married to someone else.) And while Hartnell employed his signature ballgown silhouette when it came to designing this wedding gown, it differed markedly from his other earlier designs. The long-sleeved dress featured a tight bodice, deep V-shaped neckline, and a far more voluminous skirt than had been used for Queen Elizabeth’s wedding gown. But when compared to his more ornate works, it reads as relatively unembellished; a sign of the times, perhaps, but also a nod to Princess Margaret’s more modern style.

Ultimately, as the 1960s marched on and the Mod movement took over, Norman Hartnell’s personal aesthetic fit in less and less. He continued to work, received the title “Sir,” and passed away in 1979. Despite the fact that he served as the official dressmaker to two twentieth century queens, his house has not been carried on in his name like other fashion design contemporaries such as Dior or Balenciaga. (In comparison, it seems inconceivable that Sarah Burton’s work for Alexander McQueen could find itself in a similar situation in fifty-plus years.) His legacy, therefore, has remained mainly in fashion lectures and historical books. Thankfully, The Crown has finally changed that and given Hartnell his much deserved due.

—Madeleine Luckel